Courageous Conversation: Understanding How Systems of Power Contribute to Abuse in the Church

Awake’s latest Courageous Conversation, held last week, offered an important exploration of systems of power and their role in abuse in the Catholic Church. A recording of the event is available below.

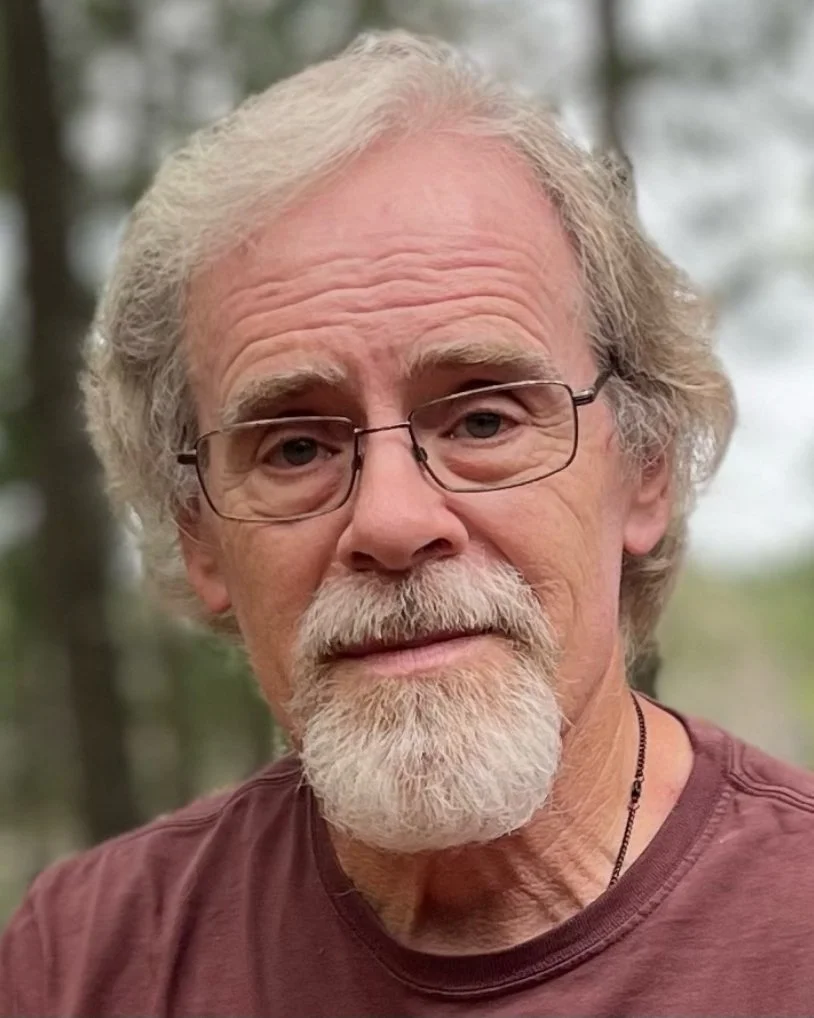

Dr. Phil Monroe

The panel included psychologist Phil Monroe, who spent many years in private practice with Diane Langberg, author of When the Church Harms God’s People, and theologian Christine Way Skinner, a doctoral candidate at the University of St. Michael’s College, veteran of more than 30 years in Catholic parish ministry, and board member of the Canadian group Concerned Lay Catholics.

The discussion also included two committed members of the Awake community. Natalie Pucillo is currently pursuing a Master of Divinity degree at Loyola University Chicago’s Institute of Pastoral Studies, and has chosen to remain engaged with Catholicism after surviving abuse by a lay minister in early adulthood. Tim Ehlinger recently retired after a 32-year career at the University of Wisconsin—Milwaukee where he was founding director of the Master of Sustainable Peacebuilding degree program and the Institute for Systems Change & Peacebuilding. He hopes to promote justice and healing by leveraging his professional experience in community transformation with his personal experience as a 14-year-old who endured sexual abuse by a priest at a summer camp.

The Importance of “Power Literacy”

Christine Way Skinner

As the conversation began, Monroe defined power as “the ability to do something, to make something happen,” pointing out that a baby exercises power by crying in the middle of the night, prompting a loved one to feed and change her. He also explained that abuse “is to misuse something, to use it wrongly,” adding, “Abuse is to treat something as an object, to use it for your own good and benefit at the disregard of the other object or thing or person.”

Skinner noted that power is not solely negative. “I think it's great to acknowledge that power in and of itself is neutral, that it can be used for good, it can be used for bad, but also sometimes it's kind of hard to tease out where the good and bad is, because often it’s a little mix of both.” Leaders may sometimes choose to bend rules or make unethical choices for what they see as the greater good, she said, calling this “dangerous territory.”

“I have met and experienced and read about and encountered many people who engaged in serious abuses of power,” Skinner said, “but almost always they had some rationalization for why what they were doing was really good.” It’s important for leaders to have a sounding board like a therapist—or maybe an honest friend or colleague—to help them see themselves clearly, to acknowledge any self-deception, and tease apart their motivations, she added.

All of this, Ehlinger said, points to the importance of “power literacy,” and the need to pay attention to how power is being used in a system or community.

Exercising and Sharing Power

Natalie Pucillo

Pucillo called attention to what she called a “false binary” of power in the Catholic Church, the mistaken impression that “priests have power and the laity don’t.” This attitude disempowers many of the people who make up the Church. She named ways of exercising power, including “teaching, preaching, programming, gathering friends for intentional conversations, writing an open letter on Substack, posting things on social media. These are all things that carry power that all of us engage in in some capacity,” she said.

Later, Ehlinger spoke about the ways leaders may limit a given conversation. “In my experience, one of the biggest types of power I see is agenda setting,” he said. “Who controls the conversation? What becomes the story and who’s at the table telling the story? In my experience with the Church, that’s a lot of what we feel disempowered to do, to [determine], as we're talking about here, what is our story of our faith?” Often people in the Church give up this kind of power, he explained, deferring to the Church hierarchy.

Monroe discussed the call to share power, rather than protecting or consolidating it. He offered an example from Acts of the Apostles, when a dispute breaks out in the early Church between the Greek and Hebrew widows; one group feels that they aren’t receiving a fair share of resources. The apostles talk about selecting a group of people of good character to oversee the distribution to widows. “If you look at the names, they appear to be coming predominantly from the minority group. So it's a handing over of power,” Monroe said. “That seems to be the way of Jesus, the handing over of power rather than the consolidating of power.”

But Ehlinger noted that institutional systems including the Church are not typically “set up to allow that type of conversation, that level of transparency.” Often there’s a fear that sharing power “is going to take away someone's position, their prestige, their power, or their influence.”

He also said that many who have experienced abuse in the Church feel that “there’s never that acknowledgement that the Church has, I’ll use the word ‘sinned,’ that there’s been a problem in part of the system.”

This led him to ask: “We can look at the abuse and the power of individuals, but at what level does the institutional system have responsibility for its behavior? Can systems be redeemed? Can they be forgiven? Do they have souls? Can they acknowledge their errors?”

LET’S DISCUSS WHAT WE HEARD. JOIN US!

Don’t miss Part 2 of this Courageous Conversation, 7 pm Central this Thursday, January 30. Attendees will break into small groups to discuss the ideas shared by the panelists in Part 1. To join us, please complete the registration for Part 2 and watch the video recording before you attend. See you on Thursday!

Could Synodality Provide an Answer?

Tim Ehlinger

Skinner and Pucillo noted that synodality could be one route to reimagining power in the Church. Pucillo explained that synodality is “the process of collaboration and discernment among all baptized members of the Church that we’ve just finished a three-year process on and are now beginning to learn how to live out.”

Structures, like people, need to grow and change, Skinner said. “Even when we put a really good system in place and it seems to be working, there will be people who will find ways to use a very good structure improperly.” She believes that there is almost always a need for reform in a system. “That’s what I really like about synodality,” she said. “It’s a process of constant discernment towards what the world needs now, which is also always changing.”

She added: “Systems change over time with the sustained effort of good people.”

At the same time, Monroe made the case that systems change can be slow. “Systems don't like change,” he said. “They tend to be self-protective. They tend to be narcissistic.” People involved in a system may acknowledge the weaknesses in the system and encourage others to overlook those weaknesses for the greater good. But Monroe suggested that letting go of a flawed system and the need for power is a more Christ-like choice. “God’s kingdom is bigger than our system and He existed before we existed, and He will exist afterwards to his glory.”

Ehlinger added his hope that synodality means “embracing these types of transparent, open conversations and bringing in the perspectives of both people who have experienced abuse and not.” He acknowledged “that there's a lot of fear that the traditional structural Church will collapse if we fully embrace responsibility for the Church's wrongdoing, when in fact,” he said, “there's hope that the Church will transform and potentially be redeemed through the work and the belief of good people working within it.”

Advice on USinG Our Power

As the event drew to a close, Ehlinger commented that there was much more to discuss about systems of power in the Church, suggesting the need for further conversations. Each panelists shared a final thought about how individuals can use their personal power to promote healing in the system of the Church.

Skinner recommended “talking and listening,” both to scholars who study the Church and people who have experienced any type of abuse in the Church. Pucillo spoke about the power of voice, both “the power that speaking out brings, positive and negative,” and “the power that staying silent brings, positive and negative.”

“I would encourage us all, and this is something that I'm working towards as well, to more regularly evaluate the reasons that we're choosing to use the power of our voices or not use the power of our voices, and to spend time discerning with the help of the Spirit where that is coming from.”

Ehlinger encouraged audience members to develop the habits of systems thinkers, as described on the website for the Waters Center.

If people feel powerless to make real change in a system like the Catholic Church, Monroe invited them to consider the example of a tiny mosquito in a bedroom. “It can keep a person awake all night, right?” he said. He encouraged audience members to dream about the possibilities for the Church and talk with others about what the Church can be. Those words might inspire only one person, he said, “but that person might help one other person, and that person might help one other person, and then we get a system change.”

Awake is a community that strives to be compassionate, survivor-centered, faithful, welcoming, humble, courageous, and hopeful. We thank you for choosing your words with care when commenting, and we reserve the right to remove comments that are inappropriate or hurtful.